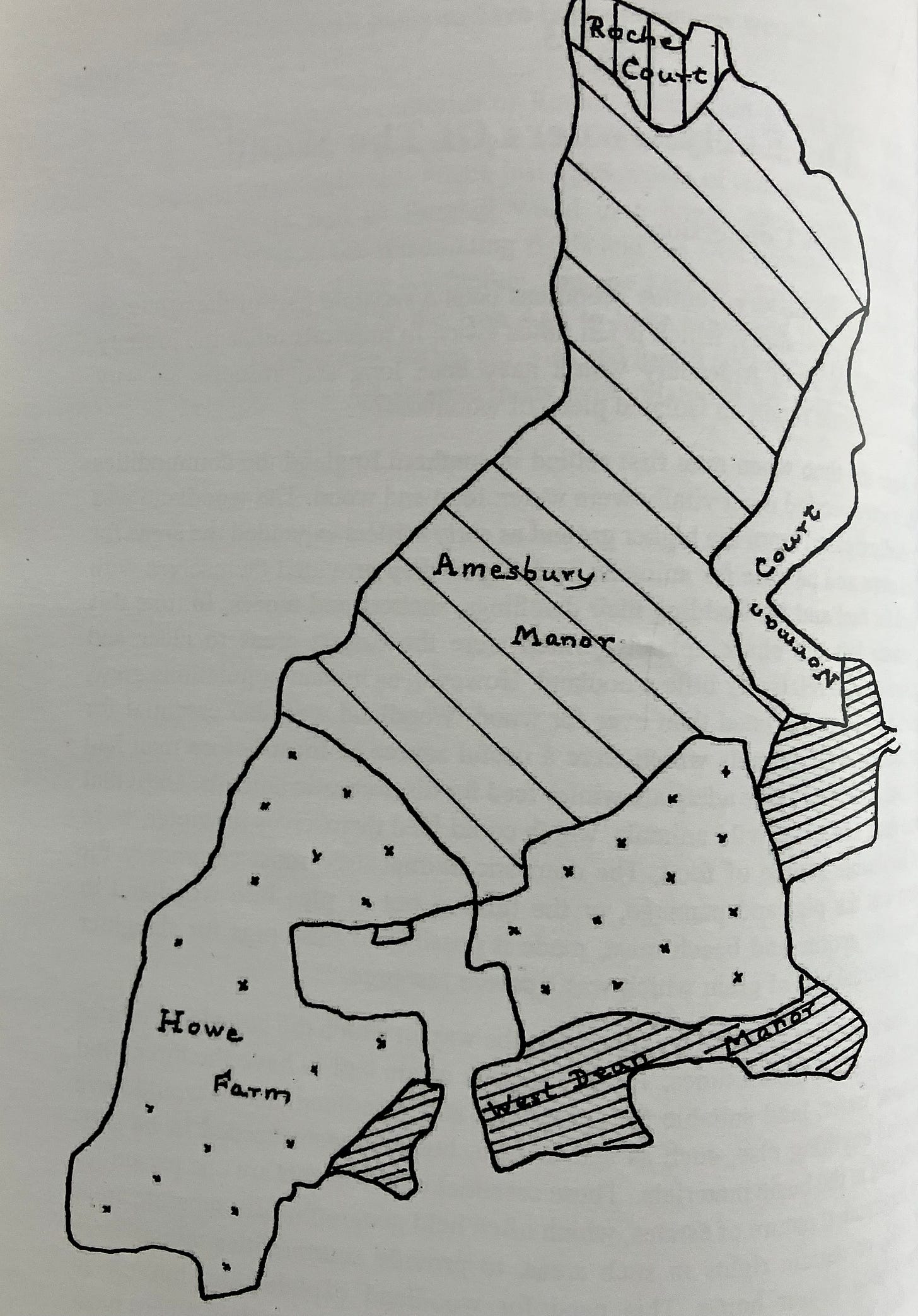

Bentley Wood was named in the The Domesday Book. It appears as one of the 29,000 acres of woodland possessed by the manor of Amesbury, or Amesbury Abbey, in 1085.

Why was Bentley Wood, a good 10 miles away and a 20-mile round trip, of interest to manor of Amesbury and its Abbey?

In the medieval period, woodland was essential to life. Trees and their products supported the physical needs of rich and poor alike. Manors looked after not only their resident families but also a very large retinue of servants, tenants and family hangers-on. The ready availability of wood meant daily survival: for heating, for construction, fencing, furniture and even for the making of bowls and cutlery.

And of course, there was the endless need for wood fuel to keep the cooking fires burning.

The pressure on woodland was therefore enormous. Other woodland owned by the manor of Amesbury was even further away, like Chute and Grovely; obviously all 29,000 acres of woodland was required to keep everyone in Amesbury and its Abbey warm and fed.

In fact, Bentley Wood must have seemed to be the nearest ‘general store’ to Amesbury and its Abbey, at least to those actually travelling to it to collect the wood.

Bentley Wood as ‘general store’ also offered a ‘meat department’’ It stocked a vital source of food, the pig. Pigs could forage for acorns and beech mast, all abundant in the Wood, making it possible to raise pigs for their meat well into autumn, when other grazing was less nutritious and cattle were therefore thinner.

Pigs at that time would have been rather like wild swine – long-legged and long-haired, with an arched, crested back and (unlike our pigs) tusks. They didn’t become valuable as meat until their third year, so would have had a happy free-range life digging up roots and nuts in Bentley before ending up in a larder in Amesbury.

The pigs would have been looked after by a swineherd, who would have trained them to return to an enclosure (or ‘pound’) at night.

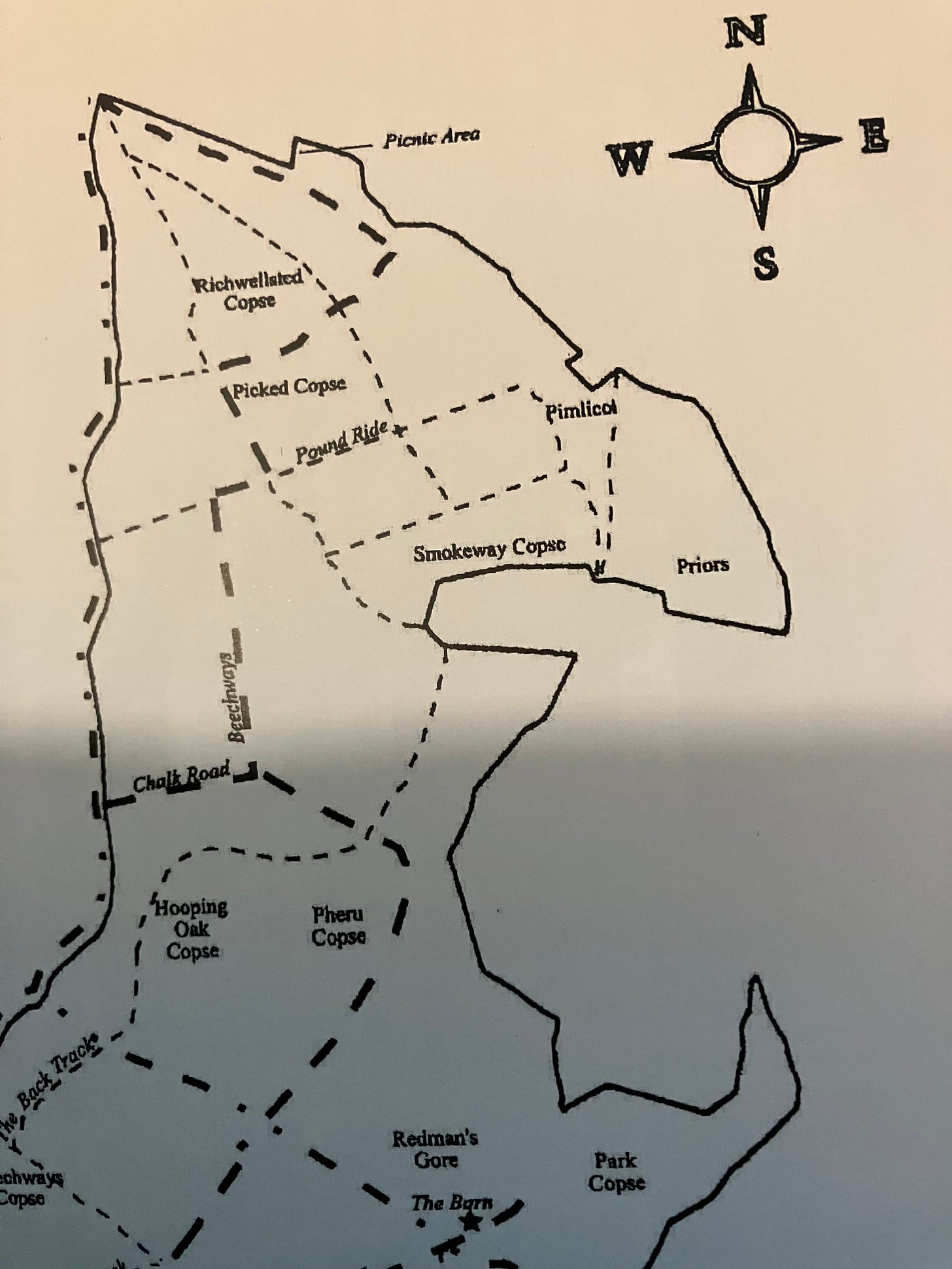

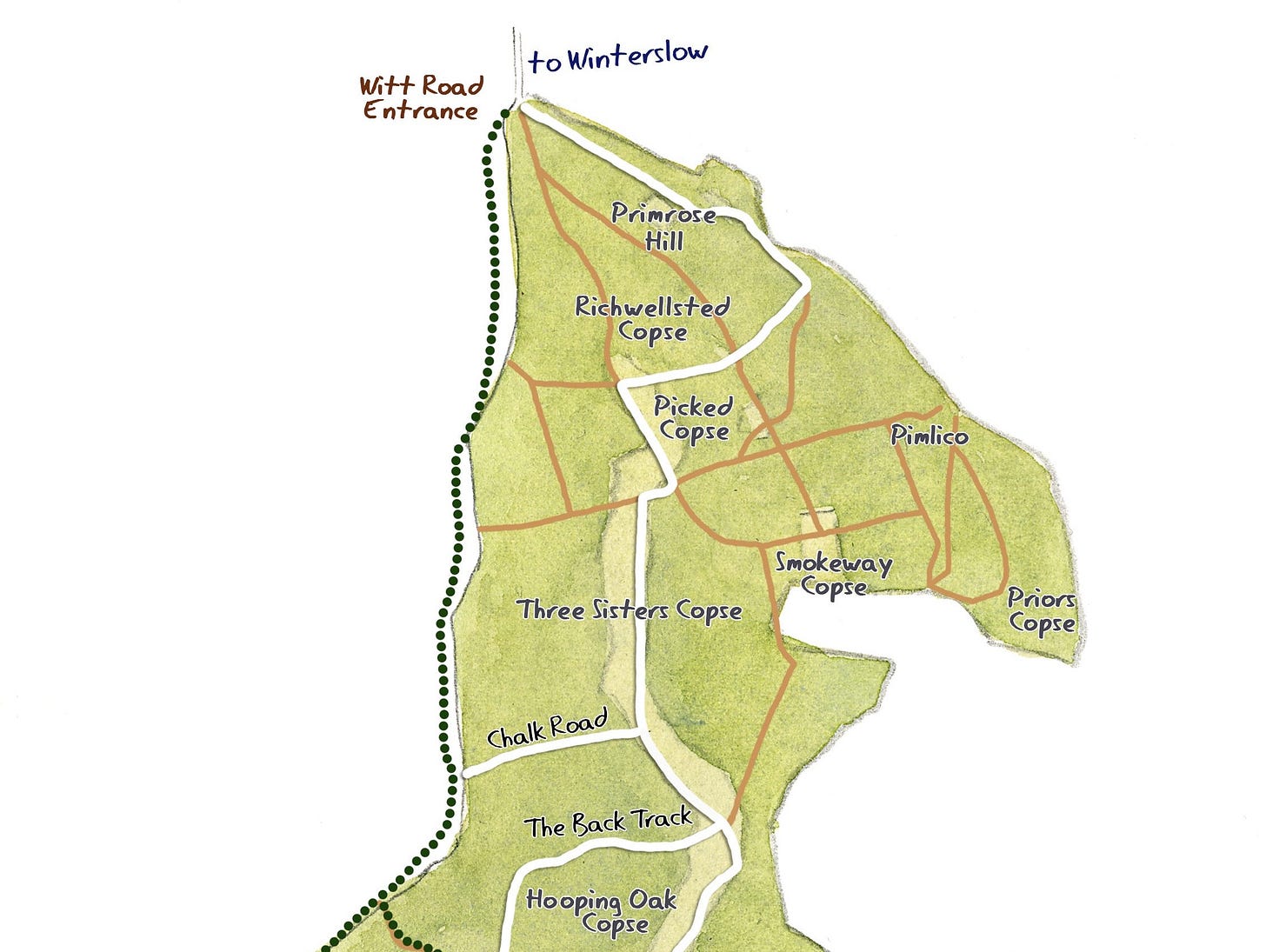

In Bentley Wood we still have the name ‘Pound Ride’ for the track along the southern side of Picked Copse, with its remains of an embanked enclosure. Perhaps this was a stockaded pen for straying or illegal animals grazing the Wood – it may even have originally been a prehistoric farmstead.

Although a trip to Bentley Wood would probably have been a better prospect for drivers and oxen than the journey to Chute, even this more ‘local’ journey must have been tiresome in summer and a terrible struggle in winter.

The marks of these struggles are still in evidence on the Winterslow ridge - in the number of deeply-cut routes we have for travelling up and down it between Pitton and East Tytherley. Perhaps there was an informal one-way system, so that ascending and descending carts did not have to risk sliding into each other on steep tracks of muddy clay or slippery chalk.

And then there was the river Bourne to be crossed, trickling or flooding. There are still four or five fords of the river Bourne between Ford and Porton, all leading to tracks heading in the Amesbury direction.

It is interesting to speculate which of our routes up and down the ridge were mainly used by the Bentley Wood to Amesbury carts. The oxen slowly pulling their cartloads of wood from the eastern side of Bentley Wood perhaps went up Witt Road, through what is now the Common in Winterslow, and down the hill via our now tarmac road to the modern A30 at the old Pheasant Inn and from there over Porton Down.

Or perhaps they kept to the dry hill-top and went via East Winterslow and down the modern byway to the road to the A30, or down the steep, deep road past Old Roche Court.

Another route could have been down the Roman road past Middleton Manor, passing modern Firsdown to get to the bridleway that passes west of Figsbury Ring. This leads to a ford of the river Bourne (at the tellingly-named Ford) or perhaps the ford at Winterbourne Dauntsey was used.

As we travel these deep ancient roads in our cars, or in our wellies, it is easy to underestimate the extent of the toil and trouble necessary to haul carts up and down them to provide the manor of Amesbury with its fuel, food and furniture.

In 1177 King Henry II, husband of Eleanor of Aquitaine, founded a new order of nuns at Amesbury Abbey. He established a Priory in place of the old Abbey. He brought in 24 nuns from Fontevrault in France to replace local Abbey nuns, who were apparently misbehaving.

The new French nuns must have felt cold. (Eleanor of Aquitaine, imprisoned by her loving husband at Amesbury for a time, certainly complained to him of the cold during her enforced stay.) The nuns were granted the right to one cartload of wood per day from woodland in five different areas: Bentley, Wallop, Winterslow, Grovely and Chute.

Henry II’s nuns were also granted the right of ‘pannage’ – the pasturing of pigs – in Bentley Wood. They kept 100 of them. They were not to lack meat in their larder during the winter months. We still have the name Priors Copse in the north-east corner of the wood – perhaps this records its particular use for pannage by Amesbury Priory during this time.

From 1227 Amesbury Priory’s holding in Bentley Wood itself was reduced; it now owned only the northern part of Bentley Wood and the area of Priors Copse might well have been lost, perhaps to West Dean Manor or Norman Court. There was obviously pressure from surrounding claimants on the supplies Bentley Wood could provide.

This northern area of Bentley Wood was very important to the various owners or tenants of the Amesbury estate for the next 400 years and more.

Henry III maintained the Plantagenet interest in Amesbury Priory. He visited in 1223, 1231, 1241, 1256 and in 1270 and the Priory was specifically allowed by him to continue to take wood from all its woodlands.

For instance, in 1231, firewood was granted to the Priory out of Buckholt, Chute and Grovely woods and ‘6 quarters of nuts’ out of Clarendon Wood. The next year more firewood for the Priory kiln was granted from Grovely and in 1256 from Chute. Maybe the ‘nearby’ woodland at Bentley Wood was in a state of ‘waste’ and extra grants of wood were necessary.

Over-use of any woodland resulted in ‘waste’ – a word which then meant woodland denuded by excessive cutting. This was a widespread mediaeval problem, and one which we know Bentley Wood may well have suffered – although creating woodland waste was against Forest Law, the nuns at Amesbury Priory had a Royal charter which specifically exempted them for being fined for creating waste in Bentley Wood!

Henry III also granted wood for use to enlarge the monastery buildings; grants of timber were made in 1226 to build the infirmary chapel, in 1231 to repair the cloister and the nuns' stalls, in 1234–1235 for work on the church. Further grants of building timber followed in 1241 and 1249.

Did any of this building timber come from the oaks of Bentley Wood? It seems more than likely. The felling of mature oaks, and the work of transporting the resulting heavy beams, must have been a local sight to behold.

There is certainly a record that by 1271 six cartloads of fuel wood per week were being drawn from Bentley Wood to keep the Amesbury nuns warm and fed in their chilly Priory on the edge of Salisbury Plain.

Did the nuns ever think where it was all coming from, or visit Bentley Wood out of interest? Or was the source of their vital wood just a detail of life left to the carters – their delivery drivers.

The majority of wood used by Amesbury Priory on a regular basis was produced, as it had been since time immemorial, by coppicing and pollarding the growing trees on a 7-10 year cycle. This produced small diameter wood suitable for fuel, charcoal, fencing and hurdle making. It also produced hazel ‘wattle’, a building material used as part of ‘wattle and daub’, an infill method still found in the walls of old buildings.

After the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII (1536-1541) the Priory and manor of Amesbury was leased from the Crown by the Seymour family as a secular estate. Most of the remains of the old Abbey /Priory buildings from the 13th century, constructed with such labour from local wood, were destroyed.

The Seymour 1540 Rent Roll records their use of coppices in Bentley Wood. Interestingly the sizes of these 16th century coppices are noticeably smaller than those recorded 300 years later, in the mid 19th century. This probably reflects the greater areas of the Bentley Wood used for grazing cattle and pannage for pigs in the 16th century. Just as today some areas of Bentley Wood are fenced against deer, and young trees provided with deer-proof protection, in earlier times young trees and precious coppice also needed to be fenced off to protect them from the attentions of hungry animals, domestic and wild.

Wood from the Woodde ‘of old time accustomed’

In 1560, 20 years after the Dissolution, the renewed lease of the manor of Amesbury to the Seymour family confirmed, ‘of old time accustomed’, the continued importance of woodland products from ‘Benteley Woodde’ to its owner.

The lease also gives a tantalising detail of the Seymour’s wealth - they had carts large enough to require 3-horsepower.

All woods or fuel to be carried by two carts called ‘the bynne carts’ with 3 horses in every cart going and coming every day in summer and winter in the woods and forests of Chute, Grovely and Benteley Woodde, for the wood to be brought to the site of the monastery, of old time accustomed.’

{With acknowledgement for the use of some source material from A History of Bentley Wood by Margaret Baskerville and David Lambert, 2005}